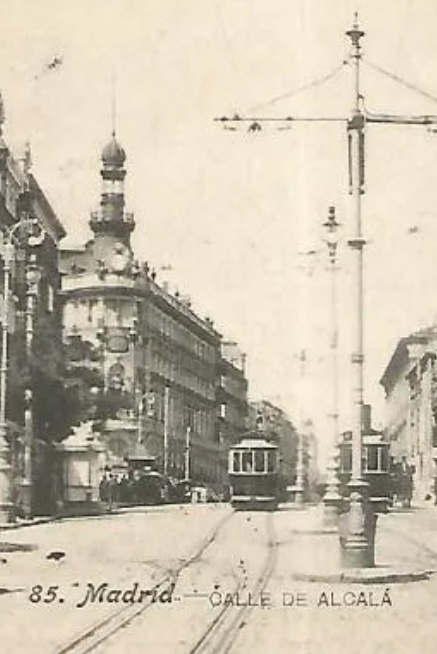

1907. Madrid. What did a tramway and an Águila beer bottle have in common?

Both relied on electricity generated in the Molinar power plant, located more than 300km away from Madrid.

In the early 20th century, electricity was already powering tram lines, factories and street lights in some cities, but most of it was DC, and its low voltage made it difficult to transport over long distances, so most power plants, whether thermal or hydroelectric, were built near the places they supplied electricity to.

The spread of AC made it possible to separate generation of electric power from the sites that used it and hydroelectric power plants, cleaner and more economical, started to replace thermal ones.

In 1907, the first hydroelectric power plant that would send electricity over great distances was built on the river Júcar, near the town of Villa de Ves. It would supply power to the tramway lines in Madrid and Valencia, and to factories like Águila brewery. At the time, it was the longest power line in Europe, and the one that carried the highest tension.

The power plant did not even require the construction of a new dam, as there was already an ancient Arab one already in place on the river and all it took was some enlargement and reinforcement. To take the water to a suitable height to move the plant’s five generators, it was carried horizontally parallel to the river’s canyon over five kilometres until it reached a height of 65 meters above the valley, from where it dropped through huge pipes into the plant.

So, what is the appeal of such a story to an adventure biker? To start with, it is an abandoned place, and that alone is enough for me to go exploring, with or without a motorbike. If we add the fact that it is located in beautiful natural surroundings, with interesting roads to get to it, even better. But what took me there was neither of those things, no.

The interesting bit is that the water did not flow over those five kilometres through your usual metal pipe, as in many other power plants in mountainous areas. It flowed through an underground canal dug in the rocks using manpower, the fruit of the work of over 3.000 men, and not just a small canal, but one large enough to allow the easy passage of a small truck without problem.

And best of all – I had heard that the access was open, so I could not miss the chance to explore it on my bike.

The first bit, the one that took water from the reservoir, is closed off with a gate, but further up the road there is a steep dirt track that goes down to the abandoned buildings of the worker’s colony where the people who built the canal and the plant lived. It was a village in itself, with church, school and a grocery store, which today belongs to Villa de Ves, the closest town, but it is in a sad state of dereliction. From there, the track goes further down with some loose rocks to the point that gives where the part of the canal that is accessible starts.

A couple of doors shut the entrance at some point in the past and a painted sign over the opening forbids people from entering, claiming it is private property, but none of that seems to discourage people, as several tire marks on the dry mud prove.

I turn on all the lights the bike has and dive into the absolute darkness, cautiously at first, more confidently as I see that the ground is dry. A moment later, light fades and I think how different this place is from the tunnels I crossed in the Alps. For one thing, here I’m riding over dry, packed terrain, which makes progress a lot easier; on the other hand, this is much, much longer. Shortly after the entrance, the gallery turns to the right and the faint light at my back disappears.

After a long while I can make out some daylight, but it is not the end of the tunnel. Two more broken doors lead into a short part of the canal that is in the open air; to my left, two floodgates that regulated flow are shut forever by rust.

Past this point, another long tunnel, another break in the open air, one last stretch of tunnel with the remains of what was once an attempt to use the tunnel to grow mushrooms, and I reach a huge cistern also dug in the rocks from where the water dropped into the plant via several pipes.

I stop the bike in front of one of the openings and I look out to see what was once the building of one of the pioneering power plants in the country, abandoned and inaccessible in the overgrown valley. There’s nothing to be found of the pipes that carried the water down there, and the same can be said of the equipment in the plant – metal is too valuable to be left to decay with the rest of the place.

Through one of the other openings I find a path that runs parallel to the tunnel on the outside of the mountain, which leads to a very steep ramp that must have been used to lower the necessary construction materials to the plant. I could have used it to climb down there, but not wearing motorbike gear, which limits my movements, not to say that I would have probably fainted climbing back up in the heat. Another time.

Back to the starting point, the dam with the same name as the power plant, I turn off the road to a hamlet called Barrio del Santuario, perched on the side of the canyon, which belongs to Villa de Ves. Before leaving the place, it is well worth to visit the Santuario del Cristo de la Vida, built atop a rock overlooking the reservoir and the dam.

A narrow winding road takes me back to the Castilian plains and as I ride away from such a peculiar place I can’t help but think what a shame it is that an infrastructure that once played such a relevant role in the development of the country should now lay abandoned and forgotten at the bottom of a canyon.

honda

honda